{field 2} | dir: {field 3} | {field 4}m

Halloween is one among many John Carpenter masterpieces that he has deigned to bestow up the world, and I have, of course, watched it many times. The rest of the sequels… not so much. As part of my annual horror movie marathon this October, I decided to get caught up the rest of the Halloween series. Much to my dismay, I discovered that much like the Friday the 13th series, the sequels to Halloween represented at best diminishing artistic and entertainment returns and at worst head-scratchingly terrible movies, the scripts for which probably wouldn’t receive a passing mark if they had had been submitted as creative writing assignments in a grade 4 class. Yes, I’m looking at you Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers and Halloween: Resurrection. These are sequels that are so bad that it felt like they were made specifically to insult and alienate fans of the series (or at least of the original film).

The Halloween sequels seemed to go off the rails almost immediately, adding increasingly nonsensical aspects to the Michael Myers mythology that made the character less impactful and the story unnecessarily convoluted. The series kept retconning itself before retconning was even a fully formed concept in pop culture. Halloween II was an otherwise solid sequel, but they retconned the backstory to make Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) Michael Myers’ long-lost sister instead of a random victim of his senseless violence in an effort to try and provide some sort of motivation for Myers’ character. This was despite Carpenter’s own original vision of Michael Myers as an “absence of character,” and more of a supernatural force of nature. Having Michael Myers obsessed with killing his own family not only didn’t make a whole lot of sense, but it also detracted from the horror of an unstoppable, unidentifiable assailant whose motivations are unclear and unknowable, who can’t be bargained or reasoned with, and who may strike again, anywhere, for any reason (or no reason at all).

After that, it was almost like tradition that each film in the series inexplicably retconned the ending of the film that came before it. By the time the sixth entry, Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers, rolled around they retconned the whole damn premise, making Michael Myers the (apparently anatomically intact) pawn of a secret cult who sent him out to kill periodically for… reasons? The irony behind the whole exercise seemed more apparent than a stolen tombstone in your parent’s bed; the more coherent they tried to make the Halloween mythology, the more completely it fell apart at the seams. One of the few saving graces for any of the sequels was the character of Dr. Loomis portrayed by the legendary Donald Pleasence, who, quite frankly, was a much higher calibre actor than any of those films rightly deserved.

It got so bad that Halloween H20: 20 Years Later, the seventh film in the series, retconned nearly all the retcons by ignoring every Halloween movie after Halloween II, including ignoring Laurie’s orphaned daughter, Jamie, and instead introducing a new timeline wherein Laurie faked her own death, moved across the country, became the headmistress of a private school, and gave birth to Josh Hartnett. Probably ignoring all of that junk in between is why H20 ranks as one of the better sequels (or at least the more coherent sequels), and even gave a fitting close to the “relationship” between Laurie and Michael. The whole sibling twist is still terrible, but H20 probably wrapped it up in the best possible way. However, any good will with the audience or artistic vision that the filmmakers built up was immediately squandered by the trainwreck that was Halloween: Resurrection, which (you guessed it) retconned the ending of H20 to make Laurie a murderer and then unceremoniously kill her off in the first ten minutes of the film so that Michael Myers can then (*checks notes*) kill a bunch of teens filming a reality show in his childhood house. It also featured Michael Myers being drop-kicked and subsequently burned in a fire by (*checks notes*) the rapper Busta Rhymes. Yep. Somebody, somewhere actually got paid real, actual money to write those things into a real, actual script.

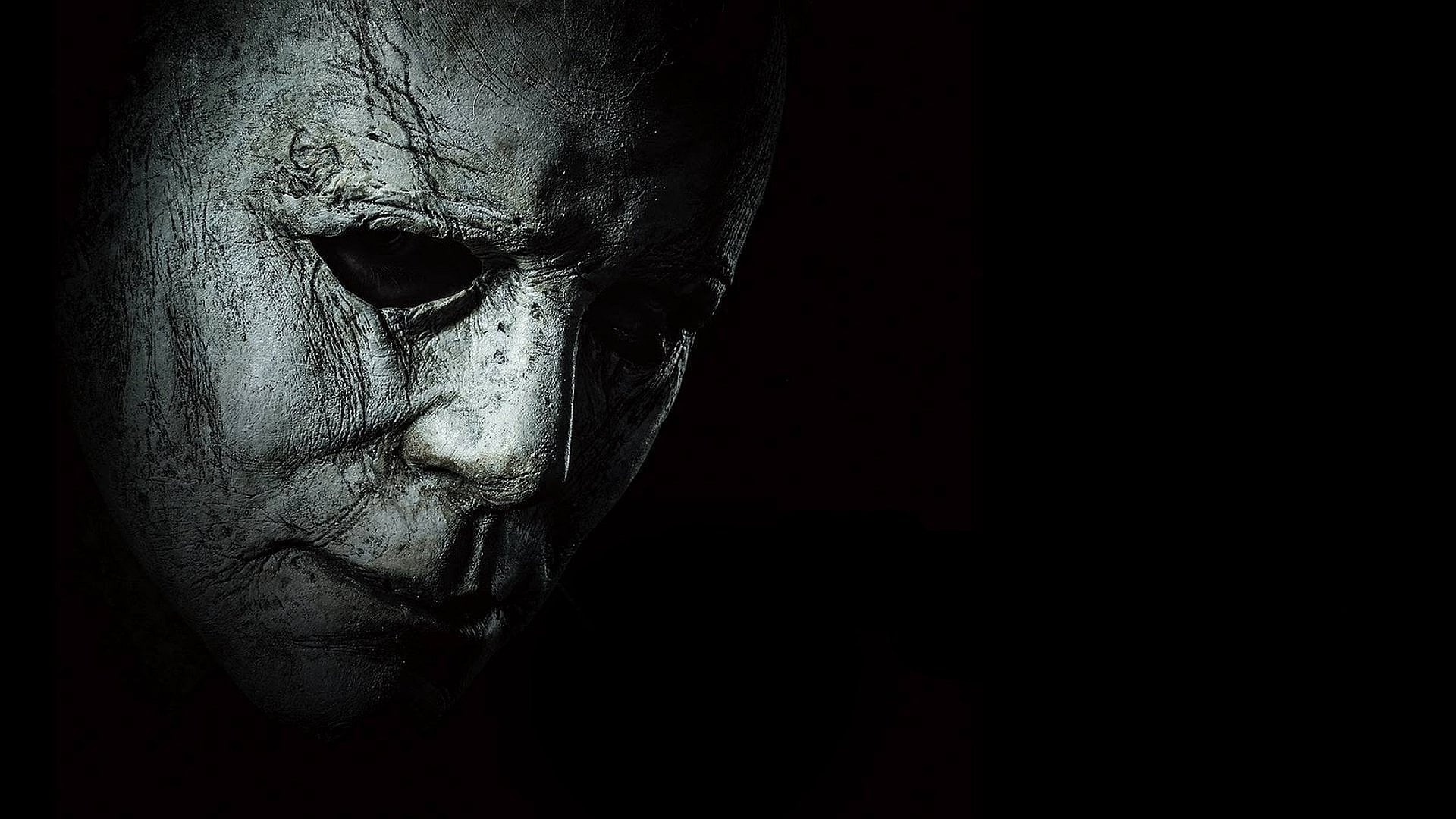

It seemed only fitting, then, that the first truly great sequel to John Carpenter’s 1978 Halloween, David Gordon Green’s 2018 Halloween, retconned the ever-loving hell out of every single one of the Halloween sequels, ignoring them all completely. Admittedly, they got kind of lazy with the naming scheme – what with Halloween being the direct sequel to Halloween – but considering how convoluted the previous sequels got and how great this one actually is, I didn’t dwell too much on the naming duplication.

Halloween 2018 picks up forty years after the original Halloween 1978, and re-established Michael Myers as an unknowable, unstoppable force of nature. It turns out that Myers was caught by police shortly after his showdown with Laurie Strode and Dr. Loomis (whose first name the Internet is now telling me is Samuel) and subsequently locked up in a mental institution as he was after he first killed his sister Judith. This time, Michael doesn’t utter a word, or really do much of anything, for forty years, reinforcing how inhuman he really is. He eventually does escape during a transfer to another facility, and goes on another killing rampage, most noticeably not against any members of his own immediate family, of whom there are none left alive. Once again, Michael Myers is depicted as more of an elemental force, an embodiment of death and a grim reminder of our transition from innocence to experience as the burden of our own mortality becomes an inescapable conclusion.

In short, Halloween 2018 was the first direct sequel of any substance, and damn fine film in its own right.

I’m not a long-time, dedicated fan of the Halloween franchise, so take this how you will. The original Halloween and Halloween III are the only previous entries that I actually truly liked (both for wildly different reasons), so maybe I’m not what you’d define as a true believer in this particular fandom. Still, as a fan of movies in general, what’s more likely to make a movie stick with me is if it is both internally consistent in its narrative logic and it has something to say, even if what it has to say is frivolous or related to a topic that I have no interest in.

Halloween 2018 is, above all, a slasher flick, another entry in a long storytelling tradition that goes back to when our ancestors would test their mettle by telling stories around a campfire. A lot of the entertainment value does, therefore, stem from the visceral exploration of human mortality (i.e., Michael kills a bunch of people). However, there’s also the right amount of rhetorical glue to hold the whole enterprise together and elevate it above other films in the genre.

One of the core themes at the heart of Halloween 2018 is the concept of trauma. As with a lot of post-modern horror films, Halloween 2018 takes a meta approach to the Halloween world. Unlike a lot of its peers, this film actually succeeds. In a post-Scream cinematic landscape, the urge to dissect ones own mythology or comment on and subvert the tropes of ones own genre is a temptation almost too great to ignore and often leads film makers astray. Luckily, Halloween 2018 is one of the few films that doesn’t disappoint in the regard.

Early on in the film, a teenager remarks to Laurie’s granddaughter, Allyson (Andi Matichak) on how insubstantial a man who murdered five people forty years ago seems when compared to all the other horrors going on in the world with death tolls much higher. And, really, he’s not wrong. In the grand scheme of things, a weirdo in a mask killing a couple people four decades ago doesn’t seem like that big a deal.

Except, maybe, to the people he murdered.

The movie goes on to answer the question of why Michael Myers is so terrifying by showing that trauma is not relative; that is, horrific events are still horrific to the people they most directly affect even though there may be some larger horror going on somewhere else in the world. Trauma doesn’t scale.

Laurie Strode, the young girl who survived an attack by Michael Myers’ in 1978, is a grown woman in 2018 with a daughter and granddaughter. She’s also quite obviously been severely traumatized by the events of that night. She’s had trouble maintaining interpersonal relationships. She clearly has some issues with alcohol. Most notably, she lives in a fortified, self-reliant house in the middle of the woods filled with enough weapons and suppliers to make any survivalist insanely jealous. Because of Laurie’s encounter with Michael Myers, she’s basically become a doomsday prepper, albeit one that isn’t just indulging in a bizarrely intense and life-altering hobby to justify their fantasies of shooting strangers in the face in a post-apocalyptic hellscape for trying to steal their freeze-dried chicken salad. And before any actual doomsday preppers who might be reading this get ready to write me a sternly worded email (hopefully you have that solar panel hooked up correctly), let me remind you that it was the movie that used the prepper trope as social indicator of mental instability. I mean, the movie is correct, but still.

As the audience we, of course, know that Laurie’s paranoia is justified, but in the world of the film itself, this makes Laurie feel like real person. She was severely traumatized by horrific events that happened to her, like any normal person would be. The person she became was also, in some sense, birthed on that night that he came home.

This ties into the other major thematic thread of how evil inspires more evil. And also how it inspires its opposite.

Early on in Halloween 2018, Michael Myers is visited by a couple of podcasters looking for a big scoop to boost their audience. They try to provoke a response from Myers by presenting him with his infamous mask that he wore that night in ’78. This does not provoke a response from Myers, but it does send the rest of the patients in the courtyard into a frenzy, with most of them howling like lunatics on a full moon. One gets the sense that Michael Myers’ evil by its very nature begets evil.

This is made more explicit later in the film when Dr. Ranbir Sartain (Haluk Bilginer), the doctor who took over “treatment” of Michael Myers after Loomis died (and who Laurie not-so-subtly dubs “the new Loomis” at one point), murders a police officer in order to prevent him from double-tapping Myers in the skull to confirm the kill this time. It turns out that Dr. Sartain, in a desperate bid to understand a patient so impenetrable that nobody has been able to get him to utter a single word in more than half a century, is obsessed with Michael Myers and making some kind of breakthrough with him. After years of clinical observation, Dr. Sartain wants to study Myers in the wild, so to speak, and helps arrange his transfer to a new facility earlier in the film at least in part to provide him with the chance to escape (or even outright helping him escape; the film leaves this fairly ambiguous).

There’s something about Dr. Sartain’s frustration that rings surprisingly true. In the context of the movie, it feels almost like Michael Myers’ insanity is so acute that it inspires insanity in others around him. Dr. Sartain no doubt started treating Michael Myers with the best of intentions, but in the end he was the one who cracked, risking the lives of innocent people to satisfy his curiosity about Myers’ psychology.

It’s Dr. Sartain who ultimately engineers Laurie Strode’s reunion with Michael Myers to try and provoke a response and discern something about the killer’s seemingly indecipherable motivations. He even suggest some kind of symbiotic relationship between the two:

“I would suspect the notion of being a predator or the fear of becoming prey keeps both of them alive.”

Like Dr. Sartain, Laurie was also inspired by Michael Myers’ evil.

Unlike Dr. Sartain, she was inspired to fight back.

Dr. Sartain fell victim to Michael Myers’ corruption, seeking to try to understand it, to learn something from it. Laurie, through all of the trauma and the failed relationships and substance abuse and doomsday prepping never stopped fighting. She failed, certainly, and was knocked down. But she always got back up and kept moving forward. The lesson Laurie learned that there was some evil that couldn’t be understood, only destroyed. In the end, Michael Myers loses because of the determination he inspires in some of his would-be victims.

In a way, Laurie Strode does become a mirror of Michael Myers. The film goes out of its way to recreate specific shots from the original Halloween 1978 this time reversed so that Laurie takes the place of Myers. There’s an especially brilliant beat at the end of Halloween 2018 that recreates the ending of the first film, this time with Michael Myers looking out over a balcony for Laurie Strode’s body to confirm the kill only to find that Laurie vanished as mysteriously as he originally had. Laurie seems to be weak in all the ways that Michael is strong. But it seems that the reverse is also true.

Michael Myers is physically strong, feels no pain, expresses no empathy, and kills anybody who gets in his way without rhyme or reason.

Laurie Strode is physically a fifty-something woman, does, in fact, feel pain, loves her family, and is super well prepared and organized.

It’s Laurie’s fortified house and recently slightly less estranged daughter, Karen (Judy Greer), that end up helping save the day. Michael is foiled by the very things that he would never be able to have on his own.

Laurie does, indeed, turn out to be the yin to Michael Myers’ yang. The latter seems destined to keep murdering random teens, police officers, and kindly old women just trying to make a sandwich, and the former seems destined to stop him at any cost. While Michael Myers seems to be compelled to do what he does by some unknown force, Laurie consciously chooses to fight back against him, even when everybody else is trying to convince her that she’s the crazy one (all doomsday prepping aside).

Now that’s a whole lot more compelling than long-lost siblings.

Rating: 4/5